Sixteen-year-old Sahil Bacchav had just finished his tenth-grade exams when he developed terrible headaches and a feeling that his nose was blocked. He was referred to King Edward Memorial Hospital, a municipal hospital in Mumbai, where he had his tonsils removed, but he didn’t feel better and stopped eating. At one point, all he did was swallow his medicines and sleep. His weight dropped to just 25kg. Sahil was referred to Tata Memorial Hospital, a leading cancer centre in the same city, where he and his family learned he had cancer of the nasopharynx and would have to undergo radiation and chemotherapy. The radiation treatment led to oral mucositis; the inside of his mouth was inflamed and painful with ulcers, so Sahil couldn’t eat or swallow anything and was dependent on feeding through a tube to get his sustenance.

During his treatments at different hospitals, Sahil’s parents took turns to be by his side, while the other stayed home, 50 kilometres away, with his twin brother. As a consequence, his father, who works as a civil labourer, earning around $6 a day, was unable to work for more than six months, leaving the family in dire financial conditions. “We have expenses like rent, household supplies and medical expenses, and we have to take small loans to make ends meet,” says Rekha Bacchav, his mother.

Having struggled to eat for so long before his diagnosis, ensuring Sahil had a good diet was important to sustain him through treatment and promote a strong recovery. Fortunately, the family was able to get help with that, thanks to an organisation that was founded ten years ago specifically to provide nutritional support to childhood cancer patients like Sahil.

Having struggled to eat before his diagnosis, ensuring Sahil had a good diet was important to sustain him through treatment

The Cuddles Foundation, whose motto is “Beating cancer starts with eating well”, presents itself as “India’s only non-profit that helps children fight cancer with holistic nutrition”. It currently has programmes in 35 government and charity hospitals in 20 cities across India.

For Sahil, this meant access to a team of nutritionists who monitored his condition and created a plan to meet his nutritional requirements. Crucially, the foundation also provided the family with monthly rations to ensure they had access to the right food. Sahil’s condition has now improved markedly, he can eat and swallow and has gained weight, his mother says.

More than 8 in 10 children who receive nutritional help from the Cuddles Foundation were at risk of being food insecure the year before they were enrolled in the Foundation’s ‘FoodHeals’ programme, according to their 2022 study ‘Food Insecurity Screening and Childhood Cancer Management in India’. With regards to monthly income, more than half (52%) of their families earned less than $120 per month, 32% earned between $120 to $350 and 12% earned $350 to $600, the report noted.

Food insecurity threatens cancer outcomes

The impact poor nutrition can have on cancer outcomes – and the opportunities that presents for improving outcomes – has only recently begun to attract the attention that it merits. The issue was highlighted within the US setting in a 2022 JCO editorial by Theresa Hastert, assistant professor of Population Studies, who works on the Disparities Research Program, at Karmanos Cancer Institute, in Detroit.

“People undergoing cancer treatment may have specific nutritional requirements and are vulnerable to poor nutrient absorption and risks associated with inadequate nutrition, including immunosuppression, infection, and impaired postoperative healing,” she wrote.

Beyond the immediate nutritional demands of healing, people with precarious access to good food may also struggle more with the many demands required to fully adhere to their course of treatment. A 2021 study by researchers at the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York, reported that cancer patients who are food insecure are more likely to have poorer functional, social and emotional well-being and are at a higher risk for depression and more likely to have missed appointments and treatment delays and interruptions.

In 2020, in the United States, among the richest nations in the world, 13.8 million (10.5%) households were food insecure and food insecurity was higher in Black (21.7%), Hispanic (17.2%) and low-income households (28.6%) according to the US Department of Agriculture.

Studies show that approximately 15–25% of cancer patients and survivors in the US cannot rely on consistent access to nourishing food. Food insecurity has been estimated to be as high as 55–70% in low-income and medically underserved patients with cancer, and is also more prevalent among young adult cancer survivors, “who typically have fewer assets than older adults and are largely dependent on employment for both income and health insurance.”

15–25% of cancer patients and survivors in the US cannot rely on consistent access to nourishing food

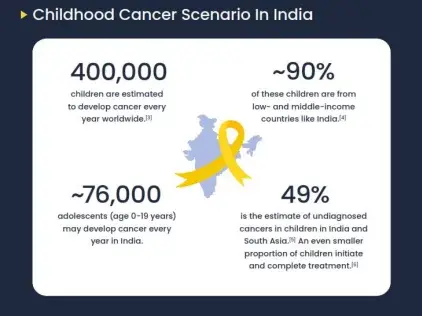

Precarious access to food remains a widespread problem at a global level, with India still accounting for nearly a quarter of all undernourished people worldwide. According to the journal Indian Pediatrics, approximately 76,000 children and adolescents develop cancer in India every year. Two in five of those children are malnourished at diagnosis, according to the study published by Cuddles Foundation in 2022, which was co-authored by Anju Moraka, the Foundation’s Head of Research, Knowledge Management and Impact.

“Food inadequacy precipitated by food insecurity can worsen the malnutrition accompanying paediatric cancers, affecting treatment outcomes,” says Moraka, who explains that the malnourishment seen at diagnosis could be due to the food insecure situation or due to the disease or a combination of both.

“Screening for food insecurity will allow for provision of holistic care with the goal of better tolerance to treatment and treatment outcomes”

Given that the response to cancer treatment depends on nutritional status, she argues, it would make sense to assess levels of food insecurity in patients and caregivers, when planning their treatment and care. “Employing food insecurity screening can help to identify food insecure households and thus allow for provision of holistic care to children with cancer, with the ultimate goal of better tolerance to treatment and treatment outcomes,” she says.

Key to the impact is not just identifying food insecurity, but being able to help provide that nutritious food, which is what the Cuddles foundation did for almost 13,000 childhood cancer patients and their families during 2021–2022, via nutritional supplements, hot meals, snacks and ration packages.

Programmes are also being trialled in some US oncology clinics to address the nutritional issues of some of their patients.

In a three-arm randomised controlled trial in four New York City cancer clinics, cancer patients with insecure access to nutritional food all had access to weekly pre-packaged grocery bags available from existing food pantries in the clinics. Further, they were assigned to either a ‘usual care control’ or to one of two intervention arms: either receiving a monthly debit card to purchase food or additional weekly online grocery deliveries. After 6 months, treatment completion in both intervention arms was higher than in the control arm: 94.6% (debit card) and 82.5% (additional grocery deliveries) vs 77.5% (controls). The treatment completion estimate among participants receiving debit cards exceeded the authors’ threshold to indicate a promising intervention. The authors also found that quality of life improved substantially, depression symptoms decreased in the grocery delivery and control arms, and food security improved in all arms.

The authors concluded that, “All interventions demonstrated the potential to improve food security among medically underserved, food-insecure patients with cancer at risk of impaired nutrition status, reduced quality of life, and poorer survival.” Echoing the call made by Moraka within the Indian setting, they suggested, “All patients with cancer should be screened for food insecurity, with evidence-based food insecurity interventions made available.”

Link for the Original article here.

Published by: Cancerworld

on February 24, 2023

Authored by: Swagata Yadavar